Alligators may help scientists learn how to stimulate tooth regeneration in people, according to new research led by the Keck School of Medicine of USC.

For the first time, a global team of researchers led by USC Professor Cheng-Ming Chuong has uncovered unique cellular and molecular mechanisms behind tooth renewal in American alligators. Their study appeared in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, the official journal of the National Academy of Sciences.

“Humans naturally only have two sets of teeth — baby teeth and adult teeth,” Chuong said. “Ultimately, we want to identify stem cells that can be used as a resource to stimulate tooth renewal in adult humans who have lost teeth. But to do that, we must first understand how they renew in other animals and why they stop in people.”

Whereas most vertebrates can replace teeth throughout their lives, human teeth are naturally replaced only once, despite the lingering presence of a band of epithelial tissue called the dental lamina, which is crucial to tooth development. Because alligators have well-organized teeth with similar form and structure as mammalian teeth and are capable of lifelong tooth renewal, the authors reasoned that they might serve as models for mammalian tooth replacement.

“Alligator teeth are implanted in sockets of the dental bone, like human teeth,” said Ping Wu, assistant professor of pathology at the Keck School and first author of the study. “They have 80 teeth, each of which can be replaced up to 50 times over their lifetime, making them the ideal model for comparison to human teeth.”

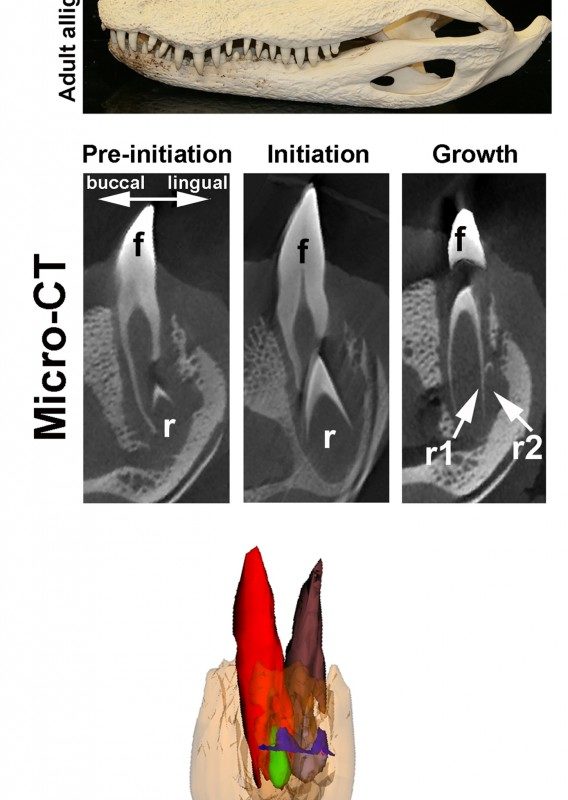

Using microscopic imaging techniques, the researchers found that each alligator tooth is a complex unit of three components — a functional tooth, a replacement tooth and the dental lamina — in different developmental stages. The tooth units are structured to enable a smooth transition from dislodgement of the functional, mature tooth to replacement with the new tooth. Identifying three developmental phases for each tooth unit, the researchers concluded that the alligator dental laminae contain what appear to be stem cells from which new replacement teeth develop.

“Stem cells divide more slowly than other cells,” said co-author Randall Widelitz, associate professor of pathology at the Keck School. “The cells in the alligator’s dental lamina behaved like we would expect stem cells to behave. In the future, we hope to isolate those cells from the dental lamina to see whether we can use them to regenerate teeth in the lab.”

The researchers also intend to learn what molecular networks are involved in repetitive renewal and hope to apply the principles to regenerative medicine in the future.

The authors also reported novel cellular mechanisms by which the tooth unit develops in the embryo and molecular signaling that speeds growth of replacement teeth when functional teeth are lost prematurely.

Co-authors included colleagues from the Louisiana Department of Wildlife and Fisheries, University of Georgia, National Cheng Kung University, National Taiwan University and Xiangya Hospital in China.

The research was supported by the National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases (grant numbers 5R01AR042177-19, 5R01AR060306-03 and 2R01AR047364-11A1).