Petraeus—who also serves as the Judge Widney Professor at USC and Chairman of the KKR Global Institute—started his morning with a glimpse into the human brain. Faculty and students from the USC Laboratory of Neuro Imaging (LONI), the Eli and Edythe Broad CIRM Center for Regenerative Medicine and Stem Cell Research at USC, and the Zilkha Neurogenetic Institute shared innovative research highlights and progress with the general during a morning tour.

Highlighting the Brain

Judy Pa, a new assistant professor at LONI, discussed the future of disease mapping, sharing images depicting the contrast between the brains of healthy individuals and those afflicted by Alzheimer’s disease. LONI Assistant Professor Neda Jahanshad steered the conversation to global brain data networks—specifically, the ENIGMA project initiated by Professor Paul Thompson. The project’s 300 researchers are sharing brain scans and genetic information from 30,000 individuals with the goal of “cracking the neuro-genetic code” underlying diseases as various as schizophrenia, addiction, HIV and post-traumatic stress disorder.

Given ENIGMA’s heavy computing and data storage demands, Petraeus asked, “You’re not running out of storage space? Even the CIA, we actually commercially contracted out. We just couldn’t build our own cloud fast enough.” ENIGMA’s computing and data storage needs are currently handled by USC’s new Institute for Neuroimaging and Informatics (INI), which houses LONI.

Finding Better Drugs

Petraeus’ curious mind next brought him to the new Choi Family Therapeutic Screening Facility, at the Eli and Edythe Broad CIRM Center for Regenerative Medicine and Stem Cell Research at USC.

Center Director Andy McMahon and Screening Director Justin Ichida welcomed Petraeus to the facility, which is testing FDA-approved drugs on motor neurons formed by reprogramming skin cells from patients with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS), or Lou Gehrig’s disease. For reasons that are not yet understood, military veterans are more likely than civilians to suffer from this fatal disease.

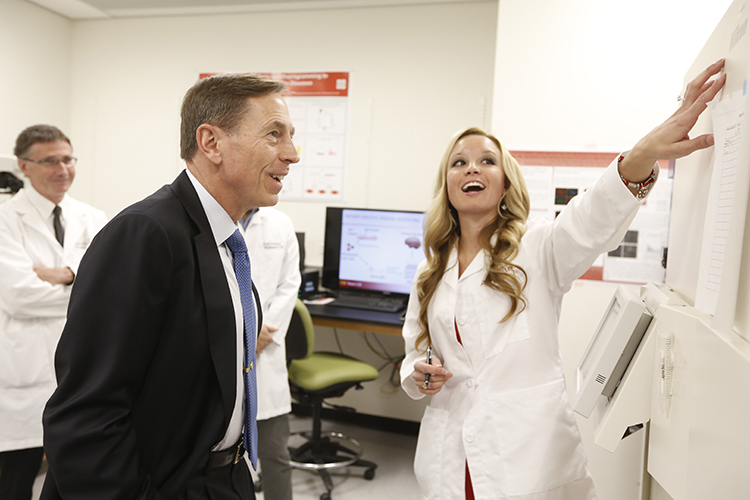

Kimberley Babos, a graduate student in the Ichida lab, showed Petraeus how to put reprogrammed motor neurons into a robotic screening machine, which exposes them to 50,000 drugs a day. The Ichida lab has already found eight FDA-approved drugs that keep the motor neurons alive in the petri dishes—indicating possible therapeutic benefit.

“This is unbelievable—robots and computers,” said Petraeus.

Professor of Research Neil Segil is collaborating with Ichida to apply a similar approach to hearing loss, which afflicts many who have served in the military. Suhasni Gopalakrishnan, a postdoctoral research associate in the Segil and Ichida labs, described how the team has used cellular reprogramming to create inner ear cells responsible for hearing. The team plans to use reprogrammed inner ear cells to search for drugs that protect against or reverse hearing damage.

“Have you gone back to Walter Reed National Military Medical Center?” asked Petraeus. “The hearing loss issue there is really important. That’s where we get our most seriously wounded combat veterans.”

Continuing his exploration of neural degeneration in its many forms, Petraeus headed to the lab of Berislav Zlokovic, director of the Zilkha Neurogenetic Institute.

Postdoctoral researcher Axel Montagne described a new test for detecting blood brain barrier (BBB) leaks, which contribute to the development of Alzheimer’s disease. A drug called 3K3A-APC, currently in a Phase 2 clinical trial for stroke victims, has shown potential for stopping these leaks in Alzheimer’s patients.

Meeting the Troops

Petraeus did get a chance to relax a bit over lunch, which he shared with several students from the Keck School who are also members of the armed forces. After getting to know each of them, Petraeus shared a piece of advice that has served him well, which is to leave their intellectual comfort zones as often as possible and never fear bucking convention.

One of the students, Katie Ross, said this advice will stay with her as she finishes school and faces career decisions. “Being able to meet him is something I will remember for the rest of my life,” she said.

Petraeus also paid a visit to the USC Navy Trauma Training Center, a program of the U.S. Navy, the Keck School of Medicine of USC and LAC+USC Medical Center, which provides armed forces medical caregivers—including medics, nurses, physicians and Special Forces personnel—crucial first-hand experience treating traumatic injuries. While there, he swapped war stories with the nurses, doctors and medics from the U.S. Navy who spent several weeks at the training center at LAC+USC before being deployed.

The general himself is no stranger to battlefield injury. Petraeus, who spent most of his career in the U.S. Army with the 101st Airborne Division, broke his pelvis in a parachuting accident, and was shot in a training accident and required the insertion of a chest tube without anesthesia. The pain and severity of the second injury, he said, was so extreme that he wasn’t sure he would survive.

“I will never forget staring into the eyes of that Army medic,” recalled Petraeus. He added that doctors, nurses and medics in the field comprise the “most important army of one” in the military.

Three trauma experts who work closely with naval medical personnel at the training center accompanied Petraeus on the tour: Demetrios Demetriades, MD, PhD, FACS, chief of the division of trauma and critical care, Edward Netwon, interim chairman of emergency medicine, and Philip Lumb, chair of the Department of Anesthesiology.

Petraeus also had the rare opportunity to step into a Keck Hospital operating room, where Inderbir Gill, executive director of the USC Institute of Urology and professor of the Catherine and Joseph Aresty Department of Urology at the Keck School, was performing a robotic surgery on a patient with prostate cancer. Petraeus, who was diagnosed with prostate cancer in 2009, marveled at the advances being pioneered at Keck Medicine of USC.

Sharing Perspective

After a full day on campus, Petraeus told Carmen A. Puliafito, dean of the Keck School of Medicine of USC, how impressed he was with HSC as a place of learning, healing and scientific discovery.

“This has to be the Delta force of health science campuses,” said Petraeus, as he finished the day by joining Puliafito on stage at Mayer Auditorium for a discussion as part of the Dean’s Distinguished Lecturer Series.

In a wide-ranging discussion, Petraeus and Puliafito discussed medicine and the military and what the two professions have in common. Petraeus noted that advances in medicine have helped many soldiers survive serious battlefield injuries, but that, too, has created challenges.

“So many come home with life-altering injuries, and their biggest challenge is not in the hospital. It is when that individual goes home and realizes that the rest of their life will be different,” explained Petraeus, best-known for leading the so-called surge strategy as commander of all U.S. troops in Iraq.

He also discussed the challenges posed by the high instance of traumatic brain injury and post-traumatic stress disorder.

At the conclusion of his visit, Puliafito presented Petraeus with a token of his appreciation: an engraving of a painting depicting the death of Joseph Warren, who died fighting British forces at the Battle of Bunker Hill. Puliafito chose a depiction of Warren to remind Petraeus of his visit to HSC, because Warren was a commissioned general, as well as one of Boston’s finest doctors.