Science fiction author Margaret Atwood has frequently stated that biotechnology itself is neutral. It is how people use it that is good or bad. In the new spring course MEDS 380 Stem Cells: Fact and Fiction, this concept became a touchpoint for discussions of everything from clones to chimeras to cyborgs.

The course was offered through the minor in health care studies, which will also offer a new fall course in stem cell biology called MEDS 335 Human Development: From Stem to Sternum. Both courses are open to all majors who have taken a general biology course.

Stem Cells: Fact and Fiction, taught by Gage Crump, sparked a semester-long conversation about stem cells in film, literature and the laboratory. In recent years, many science fiction concepts have entered the realm of the possible and the actual, altering the nature of reality and carrying heavy ethical and philosophical implications.

“I wanted to take something fun and interesting for my last semester, so stem cells are fun and interesting,” said neuroscience major Flyn Kaida-Yip.

“I didn’t know anything about stem cells, and there’s a lot of controversy and a lot of topics,” said human biology major Kaitlyn Forell. “So I just wanted to explore, to take something new.”

“I was interested in this class because as a kid, my favorite movie was Jurassic Park,” said biology major Peter Lo. “I’ve always been interested in the genetic sequence they put on the projector screen and all that stuff.”

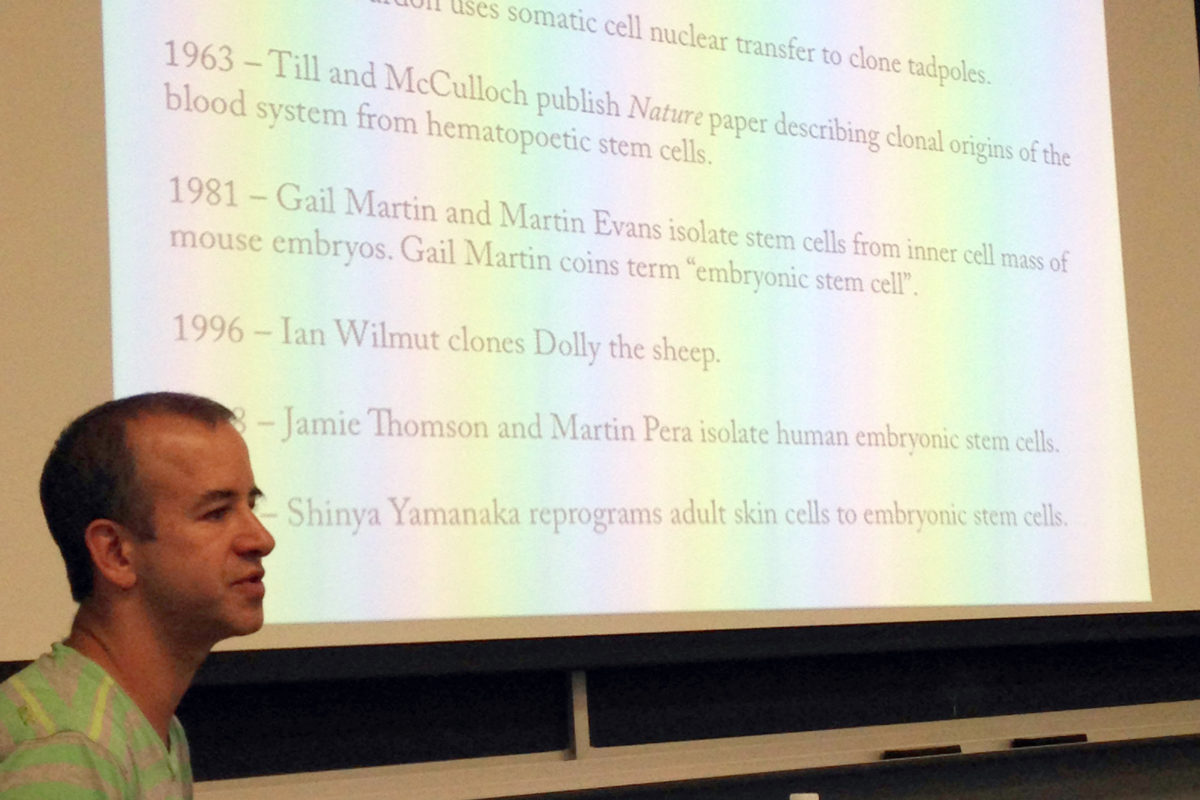

The semester started with a broad examination of cloning, encompassing both its biological underpinnings and social implications. Ever since the cloning of Dolly the Sheep in 1996, the public imagination has turned to more controversial possibilities, including the cloning of humans, and of extinct animals such as wooly mammoths or dinosaurs.

To spark a discussion about human cloning, the class read the 1976 novel Boys from Brazil by Ira Levin.

“If you have somebody who’s done great research in a certain area, would you want to clone them to have someone who can potentially carry on?” asked one student.

A classmate responded: “If you tell a child that he’s a clone of Einstein, that’s a lot of pressure!”

“But on the other hand, if we could bring back Einstein, could we also potentially bring back people we don’t necessarily want to bring back?” asked another student. “There are tons of crazy people in the world who’d want someone like Hitler back. And that kind of power is just really dangerous.”

The class then delved into the question of using new technologies to genetically engineer so-called “designer people,” such as the ones depicted in the 1997 film Gattaca.

The discussion didn’t end there. While mermaids and centaurs have long been the stuff of fairytales, human chimeras composed of cells from two different individuals have always existed.

“Essentially, this happens when two twins fuse during early pregnancy into a single embryo,” said Crump, an associate professor in the department of stem cell biology and regenerative medicine. “And so when this happens with two fraternal twins, their bodies are composed of cells essentially from two different people.”

Stem cell-based laboratory techniques are behind many other chimeras — such as animals composed of mixtures of mouse and rat cells, or of goat and sheep cells. And although the concept sounds like science fiction, mice and rats with human blood currently enable researchers to study diseases ranging from HIV to cancer.

Other sessions tackled topics including babies with three parents, cellular reprogramming, infusions of young blood to reverse aging, biological 3D printing, cell-machine interfaces and synthetic DNA. Readings ranged from Margaret Atwood’s 2003 novel Oryx and Crake to a New York Times article about lab-grown hamburgers to scientific publications.

“This is the first undergraduate course I’ve taught,” said Crump. “It’s really good to be able to take a broad overview, because stem cell biology and regenerative medicine is such a new field that people are still trying to figure out what to do with it.”