A USC Stem Cell study in NPJ Regenerative Medicine presents intriguing evidence that large bone injuries might trigger a repair strategy in adults that recapitulates elements of skeletal formation in utero. Key to this repair strategy is a gene with a fittingly heroic name: Sonic hedgehog.

In the study, first author Maxwell Serowoky, a PhD student in the USC Stem Cell laboratory of Francesca Mariani, and his colleagues took a close look at how mice are able to regrow large sections of missing rib—an ability they share with humans, and one of the most impressive examples of bone regeneration in mammals.

To their surprise, the scientists observed an increase in the activity of Sonic hedgehog (Shh), which plays an important role in skeletal formation in embryos, but hasn’t previously been linked to injury repair in adults.

In their experiments, Shh appeared to play a necessary role in healing the central region of large sections of missing ribs, but not in closing small-scale fractures.

“Our evidence suggests that large-scale bone regeneration requires the redeployment of an embryonic developmental program involving Shh, whereas small injuries heal through a distinct repair program that does not mirror development,” said Mariani, the study’s corresponding author and an associate professor of stem cell biology and regenerative medicine at the Eli and Edythe Broad Center for Regenerative Medicine and Stem Cell Research at the Keck School of Medicine of USC.

Serowoky added: “It’s still a fascinating mystery which factors or conditions result in Shh activity following large, but not small bone injuries.”

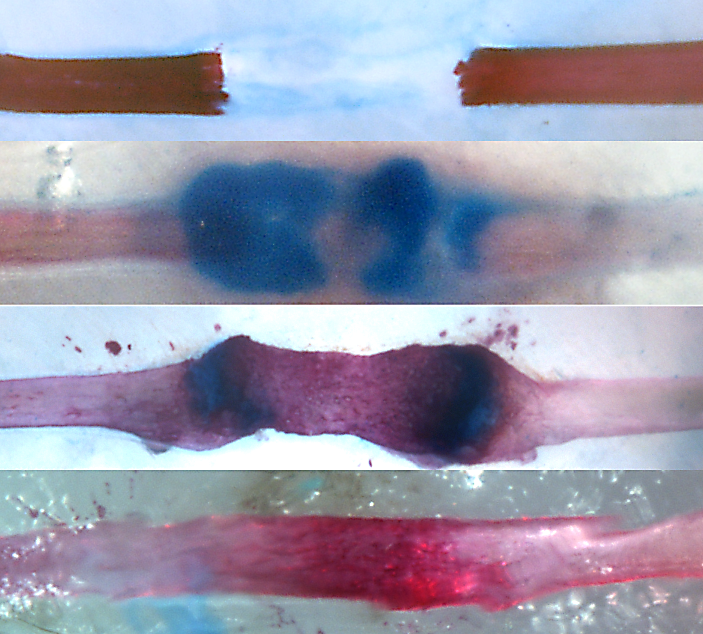

In mice, Shh activity increased briefly after a large rib injury, and then quickly returned to normal levels within 5 days. Although transient, this increase in Shh was a prerequisite for successfully building a callus, which is an initial scaffold that bridges a fracture or injury but then converts to bone and regenerates the missing section of rib. Mice genetically modified to lack Shh couldn’t successfully form calluses or heal their ribs.

In contrast, mice that had Shh at the time of injury, but were genetically altered to lose Shh after a 5-day healing period, were able to repair their ribs normally. A related gene known as Smoothened (Smo) was also required only during the first 5 days of the healing process.

The researchers expected that the source of Shh would be from specific progenitor cells that the group had previously shown to be essential for healing large injuries and that reside in the periosteum, which is the sheath of tissue surrounding each rib. Instead, they discovered that the source of Shh was an unexpected population of stem cell-like cells, known as mesenchymal cells. When these mesenchymal cells increased their Shh activity, this seemed to serve as a signal to summon a separate population of stem cell-like bone marrow cells to the injury site to assist in the healing process.

“Our discovery may inform future therapeutic strategies for situations where patients are missing large sections of bone following high energy injuries such as traffic accidents or combat wounds, or after cancer-related bone resections,” said co-author Jay R. Lieberman, chair and professor of orthopaedic surgery at the Keck School.

Additional co-authors for this USC study include Stephanie Kuwahara and Shuwan Liu from the Department of Stem Cell Biology and Regenerative Medicine, and Venus Vakhshori from the Department of Orthopaedic Surgery.

The majority of this work (90%) was supported by federal funding from the National Institutes of Health (T32HD060549, R01AR069700, R01AR057076), and the remainder was supported by a Roy E. Thomas Graduate Fellowship and a USC Regenerative Medicine Initiative Award, which provided the initial pilot funding to bring together the basic researchers and surgeon-scientists who collaborated on this stem cell study.