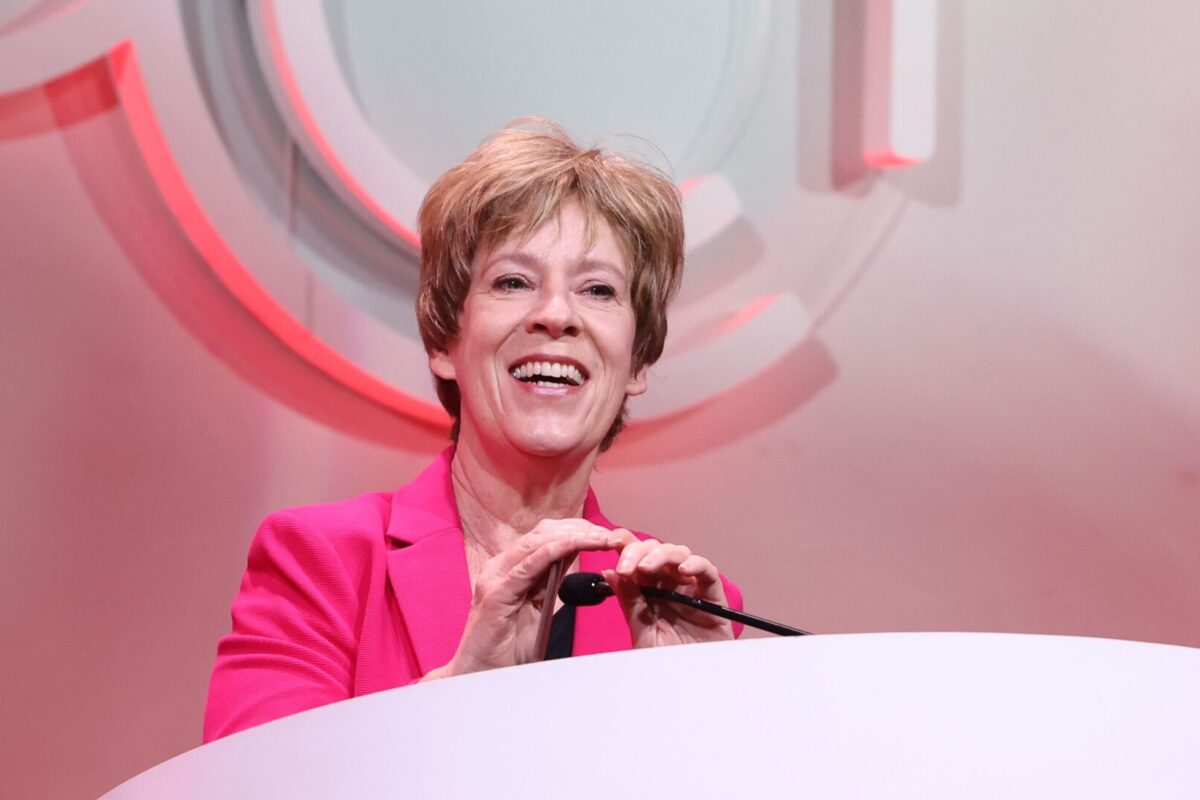

Paula Cannon, a Distinguished Professor at the Keck School of Medicine of USC, heads the world’s largest organization devoted to developing next-generation therapies that address the underlying causes of disease.

USC geneticist and virologist Paula Cannon, PhD, has become the president of the American Society of Gene and Cell Therapy (ASGCT), the primary professional membership organization dedicated to such treatments.

Established in 1996, the ASGCT has more than 6,000 members worldwide, comprising scientists, physicians, patient advocates, policymakers, and biotechnology and pharmaceutical professionals. Cannon, Distinguished Professor of Molecular Microbiology and Immunology at the Keck School of Medicine of USC, specializes in studying viruses, stem cells and gene therapies with a goal of defeating HIV/AIDS.

“I’ve been a member of the gene and cell therapy community for almost my entire academic life,” she said. “The field has grown from being like science fiction to now approaching mainstream medicine. I am delighted to have this opportunity to help continue the push to develop extraordinary, life-changing treatments for people with some of the most serious diseases.”

Gene therapies alter or replace specific spots on the DNA double-helix that have disease-causing variants, while cell therapies deploy living cells for treatment. There’s significant overlap — importantly, the potential to go beyond addressing symptoms and instead fix the source of problems underlying illness.

“I tend to think of most every human disease as having a genetic basis, including some infectious diseases,” Cannon said. “HIV can be seen through the lens of something going wrong with our genes, because the virus inserts its own genetic material and becomes a permanent genetic parasite in our body. Gene and cell therapies give us the ability to fight fire with fire.”

A turning point for emerging biomedical strategies

Research into gene and cell therapy stretches back more than 50 years. The bone marrow transplant — a treatment that reboots the immune system with healthy blood stem cells — could be considered the first cell therapy. Other major leaps in gene and cell therapy were slow in coming thereafter.

Happily, the tide is turning.

“We’ve had a very long lag phase with a lot of promise and anticipation,” Cannon said. “We’re about to reap the benefits, all over the world. The more experience we have, the more we can see what’s working and be reassured about safety. And the cost of developing new therapies will come down because companies will be able to piggyback on what’s already been done.”

Today, the basic idea behind the blood stem cell transplant — a remedy with cells that are removed from and returned to the body — remains a template for many gene and cell therapies. Such is the case with CAR T cell therapy: Patients’ own immune cells are harvested, genetically altered to amp up their cancer-fighting activity, then expanded and reinfused. In 2017, CAR T cell therapy gained U.S. Food and Drug Administration approval to treat leukemia and lymphoma.

“CAR T cells have absolutely revolutionized treatment for certain blood cancers,” Cannon said. “People are alive today who would have faced a death sentence in the past. It’s an extraordinarily powerful demonstration of what we can do when we combine genetic engineering with the ability to grow cells outside of the body and then put them back.”

The CRISPR gene editing technique that garnered the 2020 Nobel Prize in Chemistry is among recent advances that have accelerated progress, leading to high-profile successes. The FDA approved two milestone cell-based gene therapies for sickle cell disease in December 2023, and one was the first approved gene therapy made with CRISPR.

An abundance of emerging treatments waits in the wings. ASGCT counts 4,000 gene, cell and RNA therapies under development. Many seek to extend CAR T cell therapy to more cancers as well as HIV/AIDS and autoimmune disease. Cancer is a major focus of gene and cell therapies overall, but a growing proportion tackle rare diseases and conditions such as Parkinson’s disease, arthritis and type 1 diabetes.

“We are hitting exponential growth,” Cannon said. “People are giving reign to their imagination, knowing that if they can figure out how to correct that gene and a way to get the treatment into a body, there’s nothing to stop them from coming up with a way to cure people, no matter how rare or awful the disease is.”

Trojan researchers at the vanguard of attacking disease at the root

The new ASGCT president highlights building momentum in gene and cell therapy investigations at the Keck School of Medicine and at USC overall.

During the same March meeting in Baltimore where Cannon became ASGCT president, a forthcoming addition to the Keck School of Medicine also took center stage. The Presidential Symposium featured keynote remarks from Chuck Murry, MD, PhD, who will become the director of USC Stem Cell in August. Invited to deliver the prestigious address by Cannon’s predecessor, Murry works to combat heart failure using stem cells and tissue engineering.

“USC’s position as a player in the gene and cell therapy world is reflected in our ability to attract a translational scientist like Chuck Murry, who’s determined to take these tools and come up with a way to cure damage from heart disease,” Cannon said. “USC has more assets in this space than we’ve ever had before.”

In one example, a partnership uniting the medical school with Children’s Hospital Los Angeles and the Keck Medicine of USC medical system has yielded a facility for manufacturing cell therapies. Opened early last year, the USC/CHLA cGMP Laboratory offers scientists and clinicians the capability of working with customized cell therapies whether they’re developed elsewhere or homegrown by their research teams.

She also cites the importance of studies underway at the USC Schaeffer Center for Health Policy & Economics examining business decisions and payment policies around gene and cell therapies. It happens that USC has even influenced the public discourse in this area, through the lens of patients and families.

The New York Times published a February op-ed by Elizabeth Currid-Halkett, PhD, holder of USC’s James Irvine Chair in Urban and Regional Planning. Her call for changes to insurance policy and regulatory procedure were anchored in her experiences during her son’s treatment for Duchenne muscular dystrophy, a fatal and previously incurable muscle-wasting syndrome. She saw a breathtaking turnaround within weeks thanks to an investigational gene therapy — “science at its very best,” Currid-Halkett wrote, “close to a miracle.”

Cannon looks forward to playing her own part in healthy, happy endings to formerly bleak stories, through her own science and her leadership at the ASGCT.

“It’s a society that attracts dreamers,” she said. “It’s full of people who want to cure diseases. This is what motivates them, and I’m certainly the same way. If I change one person’s life through my work, that’ll be good enough for me.”

Learn more about research at the Keck School of Medicine of USC.