We all know someone affected by arthritis—as well as that old dog down the block. But according to a new study in eLife, arthritis is much more widespread in the animal kingdom than previously suspected.

In the study, Amjad Askary and Joanna Smeeton from the USC Stem Cell laboratory of Gage Crump took a close look at the evolutionary origin of the type of lubricated joint, known as “synovial,” that provides mobility yet is highly susceptible to osteoarthritis.

Scientists had widely assumed that synovial joints—such as the ones in the knees and hips—evolved in limbs when the oceanic ancestors of humans first started crawling on land. However, Askary, Smeeton and colleagues surmised that water resistance also places considerable strain on joints and decided to examine whether fish have the same types of lubricated joints found in humans.

Four-limbed bony vertebrates such as humans evolved from what are known as the lobe-finned fishes. However, no good laboratory model exists for this group, so instead the researchers focused their inquiry on a member of the more evolutionarily distant ray-finned fishes—the zebrafish, a common subject of medical research.

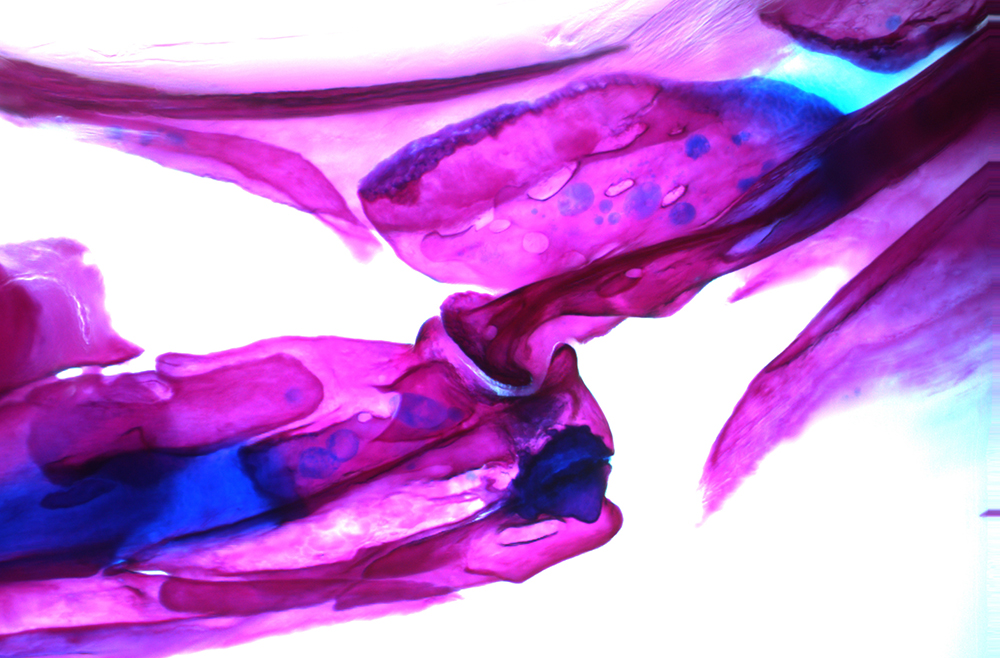

Using CT scans and sophisticated genetic tools, the researchers observed that certain joints in the zebrafish jaws and fins have features similar to mammalian synovial joints. This was not only true for zebrafish, but also for two other ray-finned fishes—the three-spined stickleback and the spotted gar. They then showed that these fish joints produce a protein very similar to the one that lubricates joints in humans —which is aptly named Lubricin.

Previous research showed that humans and mice lacking Lubricin have poor joint lubrication and develop early onset arthritis. Askary, Smeeton and colleagues found that removing the Lubricin gene from the zebrafish genome causes the same early onset arthritis in their jaws and fins. Given that fish and humans diverged hundreds of millions of years ago, when bony vertebrates first evolved, this similarity in arthritis susceptibility reveals that synovial joints are at least as ancient as bone itself.

“Zebrafish are becoming a popular system for human disease research, yet it had been thought that they lacked lubricated joints and could not be used to study arthritis,” said corresponding author Gage Crump, associate professor of stem cell biology and regenerative medicine. “Creating the first genetic osteoarthritis model in a fish is exciting. Going forward, it will be fascinating to explore whether the zebrafish, which is well known for its regenerative abilities, can also naturally repair its damaged joints. If so, the fish could teach us fundamentally new lessons in how to reverse arthritis in patients.”

Additional co-authors include Sandeep Paul and Simone Schindler from USC; Ingo Braasch from the University of Oregon, Eugene, and Michigan State University; John Postlethwait from the University of Oregon, Eugene; and Nicholas A. Ellis and Craig T. Miller from the University of California, Berkeley.

Support came from a California Institute for Regenerative Medicine (CIRM) Training Fellowship and a Wright Foundation Award.