Researchers are hard at work building mini-kidneys from human cells—using blueprints mostly drawn from lab mice. But mouse kidneys differ from their human counterparts in more than mere scale, as detailed by the USC Stem Cell laboratory of Andy McMahon in three studies in the Journal of the American Society of Nephrology.

“In mice, the kidney develops over a period of approximately two weeks, resulting in the formation of 16,000 filtration units called nephrons,” said first author Nils Lindström. “In humans, this organ forms over a period of approximately 32 weeks, during which one million nephrons form. While mouse and human nephrons show some similar patterns of development, it’s not entirely surprising that we also observe some major differences between these species.”

On the macro level, there are developmental differences in scale, timing and basic structure. For example, the human kidney possesses lobes, which the mouse kidney lacks.

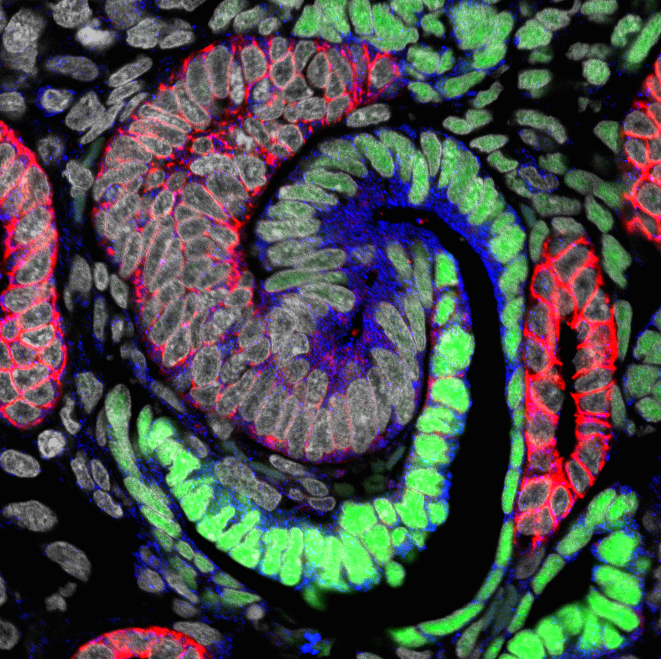

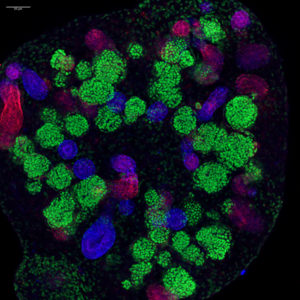

On the micro level, developing human kidneys also feature a greater diversity of cell types, and major differences in stem cell-like progenitors that build much of the kidney: nephron progenitors that generate functional nephron units, and interstitial progenitors that give rise to a variety of cells that connect the tubular networks of the kidney.

Lindström and his colleagues also noted differences in the activity of what are known as “anchor genes,” which scientists use as points of reference to determine the identity of various cell types. For example, in the developing mouse kidney, interstitial progenitors can be identified on the basis of high activity of a gene called FoxD1. Surprisingly, in the developing human kidney, both interstitial cells and nephron progenitors have high FOXD1 activity. Therefore, scientists relying on FOXD1 as an anchor gene will likely misidentify the cell types in developing human kidneys. Further, given the regulatory actions of FOXD1, and other genes that show similar behavior, the findings raise important questions about the different states of mouse and human nephron-forming progenitors.

“Only three out of 26 anchor genes conserve mouse-like activity in the human kidney,” said Lindström. “Furthermore, some of these anchor genes are implicated in kidney diseases, including cancer, that affect humans. So attempts to replicate mouse-like gene activity in human cells could have unintended consequences.”

The researchers chronicled several other similarities and differences in how this exquisitely complex organ develops in mice and humans. The three studies are: “Conserved and divergent features of human and mouse kidney organogenesis,” “Conserved and divergent molecular and anatomic features of human and mouse nephron patterning,” and “Conserved and divergent features of mesenchymal progenitor cell types within the cortical nephrogenic niche of the human and mouse kidney.”

In another McMahon Lab study published in PLoS Genetics, postdoctoral fellow Lori O’Brien, graduate student Qiuyu Guo and their colleagues focused on mouse kidney development. They identified regions of the genome, conserved between mouse and man, that regulate the genes that control nephron progenitor cells during kidney development. Much of human disease is thought to reside in changes in this regulatory component of the mammalian genome.

“When I moved to USC from Harvard in 2012, I decided to focus all our efforts towards the kidney and human kidney disease. The support of the California Institute for Regenerative Medicine, as well as the National Institutes of Health, was essential to our change in direction. Realizing the need to bridge a critical gap between model systems and man, the group has pioneered systematic, high resolution molecular and cellular approaches to understand how this key organ is built. The research provides important information to guide efforts to understand this organ in health and disease, as well as to engineer human kidney structures in the laboratory. I have a wonderful team, and these four papers are a testament to their outstanding collaborative efforts,” said McMahon, director of the Eli and Edythe Broad Center for Regenerative Medicine and Stem Cell Research at USC.

Co-authors on the JASN studies include: Jill A. McMahon, Jinjin Guo, Tracy Tran, Qiuyu Guo, Elisabeth Rutledge, Riana K. Parvez, Gohar Saribekyan, Robert E. Schuler, Christopher Liao, Albert D. Kim, Ahmed Abdelhalim, Seth W. Ruffins, Matthew E. Thornton, Brendan Grubbs, Guilherme De Sena Brandine, Andrew Ransick, Andrew D. Smith, and Carl Kesselman from USC; and Laurence Basking from the University of California, San Francisco.

For the JASN studies, support came from the California Institute for Regenerative Medicine (CIRM LA1-06536), the National Institutes of Health (NIH DK107350, DK094526, DK110792, 1U24DK110814), and the Joint Medical/Research Council/Wellcome Trust (099175/Z/12/Z). Elisabeth Rutledge had a National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Disease Award (F31DK107216), Albert D. Kim had NIH support (5F32DK109616-02) and a USC Stem Cell Hearst Fellowship, and Qiuyu Guo had a USC Research Enhancement Fellowship.

Co-authors on the PLoS Genetics study are: Qiuyu Guo, Emad Bahrami-Samani, Sean M. Hasso, Young-Jin Lee, Alan Fang, Albert D. Kim, Jinjin Guo, Andrew D. Smith, and Anton Valouev from USC; Joo-Seop Park from Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center; Trudy M. Hong, Scott Lozanoff and Ben Fogelgren from the University of Hawaii at Manoa; Kevin A. Peterson from the Jackson Laboratory in Bar Harbor, Maine; and Ramya Raviram and Bing Ren from the University of California, San Diego.

For the PLoS Genetics research, funding was from the National Institutes of Health (DK054364, DK094526, DK085959, DK100315, HG006015, DK087852, DK100738, GM103457-8293) and the March of Dimes (5-FY14-56). O’Brien had a USC Stem Cell Broad Postdoctoral Fellowship, and Qiuyu Gong had a CIRM fellowship.