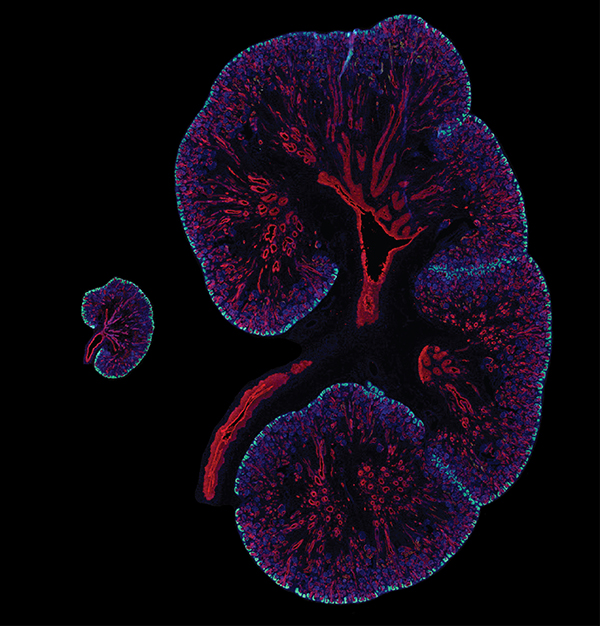

The best laid plans of mice and men are a bit different — at least when it comes to kidney development. Compared to a mouse, a human has nearly 100 times more nephrons, the functional units of the kidneys. Humans may owe these abundant nephrons to a gene called SIX1, according to a new paper published in the journal Development.

In the paper, USC Stem Cell researcher Lori O’Brien from the laboratory of Andy McMahon and her colleagues noticed that while Six1 plays a fleeting and early role in mouse kidney development, it may have a more substantial role in human kidney development.

In the developing mouse, where around 13,000 nephrons are generated over a two-week span, Six1 ceases its activity by the time the kidney has grown its first branches — right at the beginning of the two weeks.

In the developing human, where around one million nephrons are formed over a 30-week period, SIX1 remains present well beyond the initial round of branching.

Now that the researchers have proven that SIX1 lingers in the developing human kidney, the next step will be to determine what exactly it’s doing there. The researchers suspect that SIX1 is helping expand the population of progenitor cells that give rise to nephrons, but they still need to do further experiments to confirm their hypothesis.

By learning more about this process, the researchers hope to better understand both normal development and a type of pediatric kidney cancer, called Wilms’ tumor, which is associated with SIX1 mutations.

“The results of this study have highlighted the importance of examining human development, and continuing to question what knowledge we have gained from models such as the mouse,” said O’Brien. “We may find significant differences, such as in the case of SIX1, that have meaningful effects on both development and disease and will be important for driving regenerative strategies.”

O’Brien performed this research as the first of USC’s series of Broad Fellows, exceptional senior postdoctoral researchers at the transition point to starting their own stem cell laboratories. The study perfectly positions O’Brien to launch a career as an independent investigator in the near future.

In tandem with O’Brien’s fellowship from The Eli and Edythe Broad Foundation, the work was supported by National Institutes of Health grants DK054364 and DK094526, and a graduate student fellowship from the California Institute for Regenerative Medicine (CIRM) to co-author Qiuyu Guo.

Additional co-authors of the study include YoungJin Lee, Tracy Tran, Jean-Denis Benazet, Peter H. Whitney and Anton Valouev from USC.