Heinz-Josef Lenz and Min Yu both know that a cancer cell in motion doesn’t stay in motion. It comes to rest and spreads cancer.

After detaching from the primary tumor and traveling through the blood stream, circulating tumor cells take up residence in distant organs, seeding new metastatic tumors. Metastasis is the leading cause of cancer-related death.

Interrupting proliferation

Lenz, associate director for adult oncology and co-leader of the Gastrointestinal Cancers Program at the USC Norris Comprehensive Cancer Center, studies gastrointestinal (GI) cancers, with a focus on the colon. He’s found that many of the circulating tumor cells in colon cancer are either stem cell-like cells or actual stem cells — which tend to survive the initial round of chemotherapy and resist further treatment.

The reason that chemotherapy can’t kill these cancer stem cells is because they have the ability not only to differentiate into the specific cells that make up the body’s tissues, but also to self-renew, proliferating wildly and making more cancer stem cells. This ability to self-renew makes them immortal.

“The ultimate solution to really making significant strides in the treatment of cancer is figuring out how to treat cancer stem cells,” says Lenz. “And the only way to succeed in the future is creating a drug that interferes with these cancer stem cells.”

Lenz and his close collaborator at USC Norris, Michael Kahn, PhD, are well on their way to creating this drug, which is currently being tested in human clinical trials for patients with colon, pancreatic and blood cancers. The experimental drug, called ICG-001, regulates the “Wnt signaling pathway” — a group of molecules that work together to control cell functions, including proliferation and differentiation.

“Wnt is very interesting, and it’s the most important pathway in the body,” says Lenz. “When a human being develops from one cell to two, from two to four, the first pathway to initiate is Wnt.”

In more than 95 percent of colon cancer tumors, Wnt signaling has gone haywire. Lenz and Kahn’s drug corrects Wnt signaling so that it directs cells to differentiate rather than uncontrollably proliferate as they do in cancer.

Isolating and capturing cells

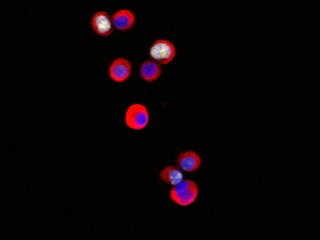

Like Lenz, Yu studies circulating tumor cells — but her focus is breast cancer.

Working with scientists at Massachusetts General Hospital and Harvard Medical School, Yu recently isolated breast cancer cells circulating through patients’ blood streams. The team of scientists managed to expand this small number of cancer cells in the laboratory over a period of more than six months, enabling the identification of new mutations and the evaluation of drug susceptibility.

If perfected, this technique could eventually allow doctors to do the same: use cancer cells isolated from patients’ blood to monitor the progression of their diseases, pre-test drugs and personalize treatment plans accordingly.

In the estrogen receptor-positive breast cancer patients in the study, Yu and her colleagues found newly acquired mutations in several genes. They then tested — either alone or in combination — anticancer drugs that might target tumor cells with these mutations and identified which ones merit further study.

In particular, the drug Ganetspib, also known as STA-9090, appeared to be effective in killing tumor cells with a mutation in the estrogen receptor gene (ESR1).

“By understanding the unique biology of each individual patient’s cancer, we can develop targeted drug therapies to slow or even stop their diseases in their tracks,” Yu said.

Yu earned her medical degree at Shadong Medical University and her master’s degree in neurology at Peking University Health Science Center.

Determined to find new treatments as a researcher, Yu joined the PhD program at SUNY Stony Brook University/Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory, where she developed an interest in breast cancer. She did her postdoctoral work at Massachusetts General Hospital (MGH) in the lab of Daniel A. Haber, MD, PhD, who was collaborating with clinicians and bioengineers to study circulating tumor cells, which enter the bloodstream and metastasize at distant sites.

“During that time, I lost my dad, because my dad had liver cancer,” says Yu. “So that made it clear to me that we need to bridge the basic research to the clinical. That’s something very, very important.”

Yu was recruited to USC in 2014 as assistant professor in the Department of Stem Cell Biology and Regenerative Medicine, jointly with USC Norris Comprehensive Cancer Center and the Eli and Edythe Broad Center for Stem Cell Research and Regenerative Medicine at USC.

Both Lenz and Yu believe firmly that tomorrow’s cures will only be realized through a close collaboration between clinicians and basic scientists.

“When clinicians and basic scientists work together, it’s actually feeding each other’s expertise and looking for the first time at things we never, ever would have done,” says Lenz. “We’re opening up new doors, new possibilities and new drug developments.”