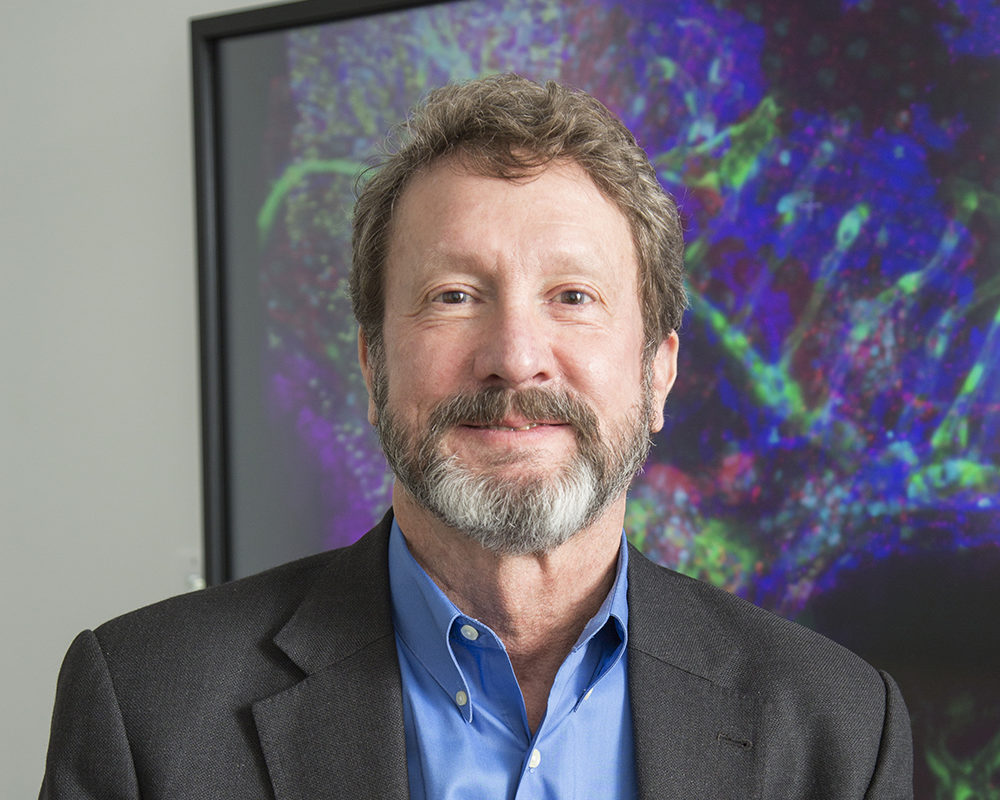

USC Professor Scott E. Fraser is known for inventing new microscopes and other tools to observe living, developing embryos. But one of his lab’s most important pieces of technology filters coffee instead of light: it’s a restaurant-quality Espresso machine.

“I wanted to make a place where people would come to steal coffee,” he said. “And they would come to steal coffee either when something really good happened, or when something really bad happened. And so you’d go have a cup of coffee, and then somebody else would be there, and they would either be elated or not elated. And if they’re not elated, you say, ‘Well, what’s the problem?’ ”

Fraser’s career-long commitment to solving problems has broadly enabled scientific discovery and earned him many accolades, most recently the 2021 Society for Developmental Biology Edwin G. Conklin Medal—the highest honor in the field.

“Our goal is to find the things that others think they can’t do, because the techniques aren’t there,” he said, “and then to go from there to figuring out how to make the techniques that are needed so we can do it. And that means we need to be versatile and fearless: building a new microscope, or building a new way of making DNA or a new way of making transgenics. It’s basically trying to redefine what’s impossible.”

A carpenter’s approach

Fraser first learned to build things as a summer apprentice to his grandfather, a carpenter who worked on big projects including a number of bridges and dams, the restaurant at the top of the tramway in Palm Springs, and the University of California campus in Santa Cruz.

“When we were building things like footings for a pedestrian bridge or repairing a dam or something like that,” said Fraser, “my grandfather would yell at me things like ‘We’re not building a piano,’ which I think translates roughly to ‘Don’t be so compulsive about things that don’t matter—match the solution to the problem.’ ”

Fraser was the “little guy” on his grandfather’s crew, meaning that he was just the right size to squeeze into tight crawl spaces under houses and other structures. Fraser considered it a great training and an even greater motivation for excelling in school: “There are only so many little spaces the little guy wants to squeeze into, with all the spiders and other fun things, before classes look a lot better.”

Fraser attended public schools in Arcadia, California, which at the time was most notable for its horses, dairy cows, and asparagus and strawberry fields. At Arcadia High School, Fraser played trumpet in the marching band. Fraser’s father, who was a policeman in Pasadena, had handed down the trumpet USC had given him when he was first chair trumpet in USC’s marching band.

At Arcadia High School, Fraser also developed a fascination with physics and what he calls “the team aspect of science.”

Although his father and brother both attended USC, Fraser chose a different alma mater and pursued his bachelor’s degree in physics at Harvey Mudd College, one of The Claremont Colleges focused on science and engineering. He worked for his tuition at a gas station, a liquor store, and the campus electronics shop.

Fraser was halfway through his undergraduate degree when biophysicist Dan Petersen joined the faculty and became a transformative mentor and lifelong friend.

“Physics, at that point was getting to be daunting: building bigger and bigger accelerators, or bigger and bigger detectors, or bigger and bigger telescopes. If you think about the budget for these things and the number of co-authors, some of the papers were like small companies,” said Fraser. “And with biophysics, a lot of the experiments were one or two people working to try to gain a new insight. And it was exciting to think about having an idea and going into the lab, and two weeks later, having an answer. I liked the smaller team and also the faster turnaround. And I loved the scale of tabletop experiments.”

Petersen not only inflected Fraser’s research trajectory, but also defined his teaching philosophy. Petersen served as an adviser to his lab members, rather than a boss.

“That’s something that I think is critical in biology and often forgotten,” said Fraser. “I think lab heads view themselves as bosses instead of advisers too often, and that teaches everybody how to be an employee instead of how to be a scientist.”

Fraser entered the PhD program in biophysics at Johns Hopkins University, and joined the same lab where Petersen had done his postdoctoral training. In the lab of R. Kevin “Skip” Hunt, Fraser once again found himself working with an adviser, rather than a boss.

“He was a wunderkind,” said Fraser. “If you’ve ever seen the movie Amadeus, and seen the portrayal of Mozart, if you put a micro-forceps in his hands instead of a piano keyboard, you would almost have my thesis adviser. He was incredibly gifted and incredibly facile and fast and everything else, but not always super stable.”

He gave Fraser the gift of independence and self-determination. When Hunt was otherwise occupied, Fraser and others in lab helped keep the lab running and gave impromptu lectures in cell and developmental biology for the undergraduates.

“I learned how to speak on my feet pretty rapidly,” said Fraser, “because you’d never know what challenge the day might hold. It went so far as having the department chair walk in and ask, ‘Where’s Skip?’ And when I said, ‘I have no idea,’ he’d say, ‘Well, he’s supposed to be lecturing to the sophomore class right now, and somebody is going to lecture to the sophomores.’ So he walked me into the classroom—on the way in, I asked to see what the reading assignment was, so I could give the lecture that day.”

Fraser not only taught biology courses, he also taught beginning and intermediate recorder through a program that Johns Hopkins called the “Free University” for students and the local community. With members of the Peabody Institute music conservatory at Johns Hopkins University, Fraser also played in ensembles called “broken consorts,” that brought together odd assortments of instruments to play early music compositions.

Back in the lab, Fraser became enamored with developmental biology when he looked at an embryo through someone else’s microscope. He abandoned his original plan to study membrane biophysics and the body’s conversion of sensory stimuli into electrical signals. Instead, he began probing the fundamental principles of how the nervous system develops.

Fraser’s view of science was shaped by attending and later teaching an elite postgraduate course in embryology, which has been offered since 1893 at the Marine Biological Laboratory (MBL) at Woods Hole, Massachusetts. The course is famous for the diversity of its students and faculty, with alumni that include Gertrude Stein and other household names like Nobel Laureate Eric Wieschaus.

Woods Hole was the Cannes Film Festival of science then.

“People, when they had a new finding, came to Woods Hole and presented it, and it got stress tested,” said Fraser. “You name the topic, there was a seminar on it, and they were all super interactive and combative. The audience would start heckling the speaker. The speaker would start heckling the audience. It was a very interesting trial by fire for a young physics person turned biologist to see how far and fast the discussions could go. And what was great about it is that people would argue aggressively with one another on topics ranging from how limbs pattern to how cells divide. After they’d been combative with each other, they’d leave together to get a drink at the local bar, the Captain Kidd. You see, it wasn’t just an argument, it was a process to figure out how the complexities of biology might work.”

At Woods Hole, Fraser first learned out how to use sharp microelectrodes to record from and to inject cells—a trick that he later used as a young faculty member to inject dyes for labeling and tracing cell lineages in developing embryos.

Fraser also conducted elaborate culinary experiments to encourage socializing and bonding among the students, postdoctoral trainees, and more senior scientists. He would wake up early to scour the markets for the freshest catches and to glean cooking tips from local fish mongers and longtime MBL researchers, such as J. P. “Trink” Trinkaus. As a result, Fraser developed legendary recipes, including a technique for barbecuing lobster with spices, lemon juice, and enough olive oil nearly to create an explosion.

“He taught me how to cook fish well,” said Richard Harland, a professor of molecular and cell biology at the University of California, Berkeley. “He’s an extremely good cook, so that’s a good property in a friend. He’s a terrific host. He’s extremely gregarious. He puts up with nothing. He has this—some might call it mischievous; some might call it cruel—sense of humor, and is always needling people. It certainly breaks the ice. You can’t help but feel like one of his best buddies, because nobody would be that mean to somebody they didn’t know.”

Over the years, many friends and collaborators have come to feel the same way about what Fraser calls his “sick sense of humor.”

“Among Scott’s alums, there’s actually a pathology where you somehow feel slighted if you’re at a conference and Scott’s giving a talk, and he doesn’t insult you from the podium,” explained John Wallingford, who did part of his postdoctoral training with Fraser before becoming a Professor of Molecular Biosciences at the University of Texas at Austin. “You actually have your feelings hurt. It’s like, ‘Well, I’m here. Andy got insulted. Why did I not get insulted?’ That’s how sick this family is.”

An early start

During his PhD at Johns Hopkins University, Fraser began gravitating to the type of high-risk, high-reward research projects that have since defined his career.

“I developed a thesis plan that had three experimental goals, all of which could have blown up in my face, and as it turns out, they didn’t,” he said. “And it was dumb luck, but they worked, so I got my degree and defended my thesis in two-and-a-half years. That was super fun, because it was a gamble, but it was a gamble that paid off, and it was a gamble that involved me doing a lot of thinking for myself.”

While he was completing his degree, Fraser visited the University of California, Irvine (UCI) to give a talk to the amazing communities of biophysicists, developmental biologists, and developmental neurobiologists blossoming there. The result was three separate job offers: Fraser soon became an Assistant Professor of Physiology and Biophysics in 1980, and eventually ascended into the role of Department Chair.

During his decade at UCI, Fraser developed imaging and other technologies to trace the lineages of cells and follow their migrations as they formed and wired the central nervous system. He collaborated with UCI’s developmental biologists to apply his tricks more broadly across a wide variety of species, including invertebrates such as fruit flies and sea urchins, and vertebrates such as mice, chickens, fish and frogs.

He also developed an enduring habit of starting his day as early as at 4 a.m.

“I could get a few hours of work done before the kids needed to be dropped off at school,” he said. “And so then I could spend the rest of the day talking to people about the experiments that failed or the tools that we needed to build, because I’d gotten most of the things done in the morning. I probably should think about making sure I get a little more sleep, but I do like relaxing, and I do like working. So I have a relatively normal evening, and then a relatively early-starting day.”

In 1991, Fraser moved to Caltech, a leaner organization where it was easier to build centers connecting medicine, engineering and the basic sciences of biology, physics, and chemistry. Over the course of two decades as a faculty member there, he succeeded in promoting cross-disciplinary research first as the Director of the Biological Imaging Facility at the Beckman Institute, then as a founder of the Caltech Brain Imaging Center and a founding member of the Kavli Nanoscience Institute, and later as the Director of the Rosen Bioengineering Center.

At Caltech, Fraser continued to develop new technologies to explore early embryonic development, and to sense the molecular basis of embryonic patterning. He and his collaborators pioneered new ways to quickly obtain high-resolution images from deep inside living embryos—using everything from souped-up and scaled-down versions of MRI machines, to microscopes that could take multi-color images that he licensed to Zeiss.

“He’s just continually pushed the boundaries of imaging development,” said Gage Crump, a Professor of Stem Cell Biology and Regenerative Medicine at USC. “The idea that we can look at a single cell resolution or even subcellular resolution now in development is largely through Scott’s work.”

Beyond the visual realm, Fraser has created other types of devices and sensors to probe living organisms. At Caltech, co-founded the company Clinical Micro Sensors to create handheld devices for detecting viral DNA as a way to quickly and accurately diagnose diseases, such as HIV/AIDS or hepatitis C. In 2000, Motorola acquired the company for approximately $300 million. Jon Faiz Kayyem, the lab alumnus who drove the company, now called GenMark Diagnostics, developed a robust test for COVID-19, so it was sold again for $1.8 billion.

“I was at Caltech [as a PhD student] a few years after he started there, and what he really did there was he built a platform for other people to pursue their big ideas,” said Andy Ewald, who is now a Professor of Cell Biology, Oncology, and Biomedical Engineering at Johns Hopkins University. “When you were a member of his lab—whether a student or fellow or research faculty member—you were there to ask big questions and do big experiments and reach big conclusions that you were interested in. You were not minions underneath him executing steps of his prior plan. So it was very much that he built an ecosystem in which the rest of us thrived. It wasn’t an environment where you were competing with each other; you were competing with posterity.”

Fraser encouraged the same style of open and critical exchange that he had experienced at Woods Hole. Lab meetings were well-known to be “trials by fire”—but if lab members could present their case clearly there, they would have experienced their most demanding audience.

Rusty Lansford—who did his postdoctoral training in the Fraser Lab and is now an Associate Professor at the Keck School of Medicine of USC, and an investigator at the Saban Research Institute of Children’s Hospital Los Angeles—has similar memories of Fraserland.

“We joined so many other brilliant scientists in an open and sarcastic climate,” said Lansford. “Scott encouraged us to have fun, take risks, work across disciplines, be brutally honest about the science, innovate, and quantitate. It seemed like anything was possible.”

A larger playground

Over the years, Fraser began to spend more and more time at USC, attracted by its clinical connections and diversity of disciplines.

In 2012, he left Caltech to become a USC Provost Professor of Biological Sciences and Biomedical Engineering, and the Director of Science Initiatives. He also has appointments in the departments of Stem Cell Biology and Regenerative Medicine, Pediatrics, and Molecular and Computational Biology, and holds the Elizabeth Garrett Chair in Convergent Bioscience.

“Part of what motivated the move was the thought that there’s a lot of unmet opportunities at USC for interdisciplinary things, and the diversity in the schools meant that it was possible to do the clinical translation much more easily,” he said. “So the attractiveness of moving to USC was just the larger playground. And the idea was to come and build more of these interdisciplinary centers, and we’ve been able to build three.”

These include the Translational Biomedical Imaging Laboratory at Children’s Hospital Los Angeles, as well as the Translational Imaging Center and the Bridge Institute at the USC Michelson Center for Convergent Bioscience.

“At USC, Scott’s has been one of the people who’s built enabling facilities to help the community access some of these great imaging resources,” said Professor Andy McMahon, Chair of the Department of Stem Cell Biology and Regenerative Medicine, and Director of the Eli and Edythe Broad Center for Regenerative Medicine and Stem Cell Research at USC.

Professor Yang Chai, who directs the Center for Craniofacial Molecular Biology at the Ostrow School of Dentistry of USC, added: “Scott has helped to champion a lot of collaborations, making these connections that we didn’t know existed. We’re very fortunate to have him at USC.”

Seth Ruffins, Director of the Optical Imaging Facility in USC’s stem cell research center, values Fraser’s exceptional “ability to pull together teams of good people” and “build things that are useful.”

In recent years, Fraser has become increasingly focused on building things that are useful not only for researchers, but also for physicians. He’s launched several startups to clinically translate technologies ranging from sensors that can detect disease-causing mutations, to imaging devices that can provide earlier diagnoses for eye disease.

At the same time, Fraser remains enamored with the fundamentals of developmental biology—whether he’s looking at an embryo through someone else’s microscope or an instrument of his own invention.

“He tinkers with microscopes, he tinkers with embryos, he tinkers with chemicals, and it all comes together in this fairly miraculous way,” said Wallingford. “So that’s the kind of guy Scott is. A lot of scientists spend 40 years trying to solve one problem, and Scott just tries to solve all the problems all the time. And that’s not a good way to be successful, but he’s been stunningly successful.”