USC scientists have developed a new tool to peer more deeply and clearly into living things, a visual advantage that saves time and helps advance medical cures.

It’s the sort of foundational science that can be used to develop better diagnostics and treatments, including detecting lung cancer or damage from pollutants. The technology is versatile enough it could become a smartphone app for use in remote medicine, food safety or counterfeit currency detection, said Francesco Cutrale, lead author of the study and research assistant professor of biomedical engineering at the USC Viterbi School of Engineering.

Scientists affiliated with the USC Michelson Center for Convergent Bioscience have been working on the technology for the past few years. Their findings are published today in Nature Communications.

The technique focuses, literally, on the building blocks of biology. When biologists look deeply into a living thing — a cell, a fish, a person — it’s not always clear what’s going on. Cells and proteins are deeply intertwined across tissues, leaving lots of questions about the interactions between components. The first step to curing disease is seeing the problem clearly, and that’s not always easy.

How this USC-developed imaging technology works

To solve the problem, researchers have been relying on a technique called fluorescence hyperspectral imaging (fHSI). It’s a method that can differentiate colors across a spectrum, tag molecules so they can be followed, and produce vividly colored images of an organism’s insides.

But the advantages that fHSI offers come with limitations. It doesn’t necessarily reveal the full-color spectrum. It requires lots of data, due to the complexity of biological systems, so it takes a long time to gather and process the images. Many time-consuming calculations are also involved, which is a big drawback because experiments work better when they can be done in real time.

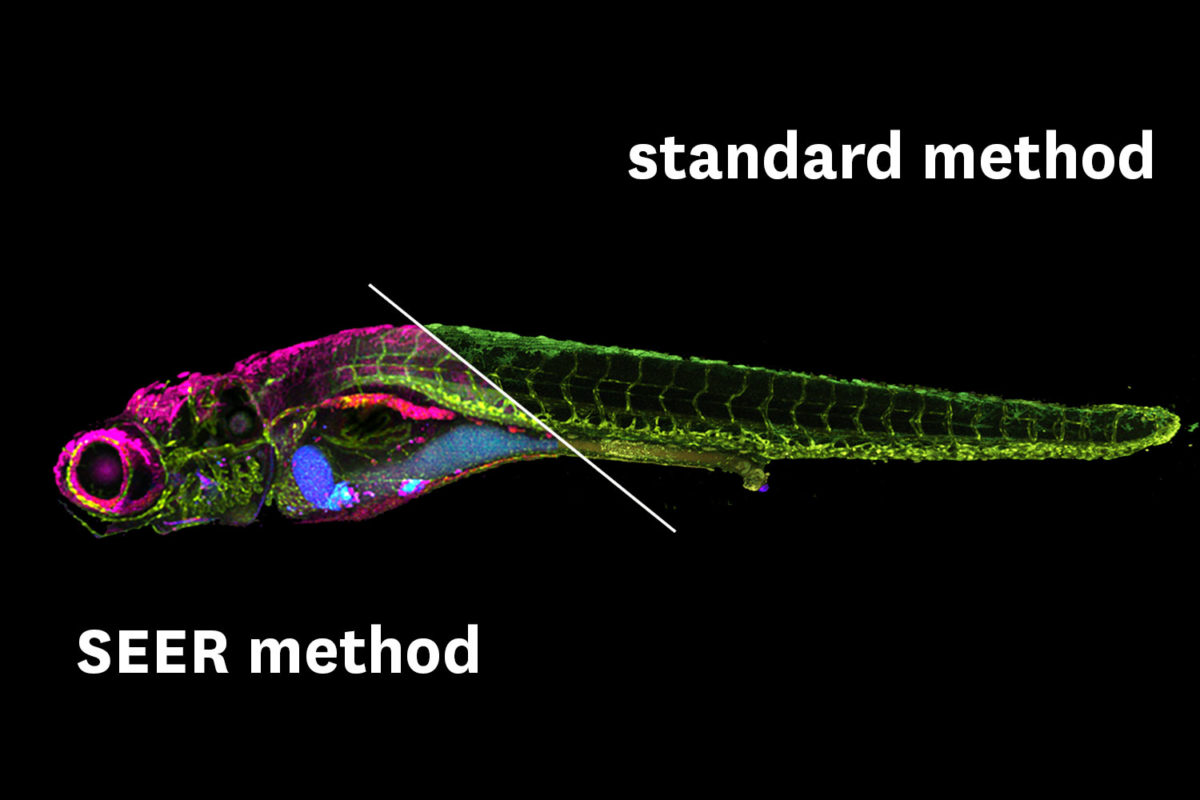

To solve those problems, the USC researchers developed a new method called spectrally encoded enhanced representations (SEER). It provides greater clarity and works up to 67 times faster and at 2.7 times greater definition than present techniques.

It relies on mathematical computations to parse the data faster. It can process vibrant fluorescent tags across the full spectrum of colors for more detail. And it uses much less computer memory storage, even more important with the explosion of big data research behind modern convergent bioscience research. According to the study, SEER is a “fast, intuitive and mathematical way” to interpret images as they are collected and processed.

“There is a number of scenarios where this after-the-fact analysis, while powerful, would be too late in experimental or medical decision-making,” Cutrale said. “There is a gap between acquisition and analysis of the hyperspectral data, where scientists and doctors are unaware of the information contained in the experiment. SEER is designed to fill this gap.”

From detecting lung cancer to potential mobile phone app

SEER’s first application will be in the medical and research field. The versatile algorithm, first authored by Wen Shi and Daniel Koo at the Translational Imaging Center of USC, will be used for detecting early stages of lung disease and potential damage from pollutants in patients in a collaboration with doctors at Children’s Hospital Los Angeles. Also, scientists in the life sciences field have started adopting SEER in their experimental pipelines in an effort to further improve efficiency.

Improvements in imaging technologies can also reach the consumer level, so it’s likely that technologies such as fHSI and SEER could be installed on mobile phones to provide powerful visualization tools.

The Michelson Center brings together a diverse network of premier scientists and engineers from the USC Dornsife College of Letters, Arts and Sciences, the USC Viterbi School of Engineering and the Keck School of Medicine of USC under one roof, thanks to a generous $50 million gift from orthopedic spinal surgeon, inventor and philanthropist Gary K. Michelson and his wife, Alya Michelson.

The study authors include Cutrale and Wen Shi, Daniel Koo, Masahiro Kitano, Hsiao Chiang, Le Trinh, Cosimo Arnesano, David Warburton and Scott Fraser of USC; Gianluca Turcatel and David Warburton of the Keck School of Medicine and Herman Ostrow School of Dentistry of USC and the Saban Research Institute of Children’s Hospital Los Angeles; and Benjamin Steventon of the University of Cambridge.

The study was supported by a Department of Defense grant (PR150666) and USC.